INTRODUCTION

The changing setting in which Chinese medicine is practiced in modern versus ancient times, especially with the advent of advanced technological medical diagnostics, has raised questions as to the value of pulse diagnosis. Should its use be limited to confirming a diagnosis reached by other means? Or, does the pulse information add critical information that can greatly alter the treatment strategy? Training in pulse diagnosis is often quite limited; further, the requisites for carrying out a traditional style diagnosis are sometimes absent from the clinical setting, making the results of the pulse taking less certain. How does one get the desired information under such circumstances?

Several years ago, an acupuncturist in the U.S. wrote to me saying:

I've been practicing for over five years now and have a busy practice; but, I'm totally disheartened about my abilities. The biggest difficulties are diagnostic. I graduated school as one of the best students in my class, yet neither I nor any of my classmates had any clear sense of tongue or pulse diagnosis. I've gone to endless seminars, but theory isn't doing it for me. All the theory is useless if you're unsure of your diagnosis. What I need is an experienced practitioner to work with who can and will tell me if what I'm seeing on the tongue and feeling in the pulse is correct. Otherwise, I feel as if I'm fantasizing all the time. Is that what Chinese medicine is all about?

This practitioner has recognized something that many others, who feel more confident despite limited training, may ignore: there is a great potential to simply "fantasize" the diagnostic signs, that is, to read into it something that is not really present. But, this is not what Chinese medicine is about; rather, there is a clearly defined method of pulse taking (and tongue examination, as well as other important diagnostic techniques) that can lead to reasonably well-defined syndrome determination.

The information presented below is aimed at examining the traditional and modern roles of pulse diagnosis, the techniques for taking the pulse, the interpretation of various pulse forms, and some of the controversies that exist regarding the use of pulse diagnosis.

THE ORIGINAL PLACE OF PULSE DIAGNOSIS IN THE CHINESE TRADITION

Pulse diagnosis is one of the original set of four diagnostic methods that are described as an essential part of traditional Chinese medical practice (1). The other three diagnostic methods are:

- inspection: general observations of the patient, including facial expression; skin color and texture; general appearance, and the shape, color, and distinctive markings of the tongue and the nature of its coating; and smelling (noting any unusual smell of the body, mouth, or urine);

- listening: to the quality of speech (including responsiveness to questions, rapidity of talking, volume of the voice); to the respiration; and to sounds of illness, such as coughing, gurgling from the intestines; and

- inquiring: obtaining information about the patient's medical history and their symptoms and signs, such as chills/fever, perspiration, appetite and dietary habits, elimination, sleep, and any pains; also, for women inquiring about menstruation, pregnancy, leukorrhea and other gyno-obstetric concerns.

All of these diagnostic methods yield information that helps to determine the syndrome and constitution to be treated. While the Chinese pulse and tongue diagnosis methods, because of their frequent mention and somewhat unique quality among traditional medical systems, receive much attention, the other aspects of diagnosis cannot be ignored or downplayed.

The Chinese term indicating a blood vessel or a meridian (which are two interlinked concepts; see Drawing a concept: jingluo) is mai, and the same term is used to describe the pulse. Pulse feeling is called qiemai, which is part of the general diagnostic method of palpating or feeling the body: qiezhen [feeling method].

Pulse diagnosis is mentioned in ancient texts, such as the Huangdi Neijing and the Huangdi Neijing of the Han Dynasty period, but with only sporadic mention of various pulse forms and their meaning. In the Huangdi Neijing, pulse is depicted primarily as a means of prognosis for impending death. As an example, in the section of the book on yin and yang it is said that (2):

A yin pulse that shows no stomach qi is called the pulse of zhenzang [decaying pulse] and the prognosis is usually death. Why? Because a yin pulse reflects absence of yang and thus absence of life activity. If you can distinguish the presence or absence of the stomach pulse, you can know where the disease is located and give the prognosis for life or death, and even know when death might occur....When yang pulses are absent in a patient, the yin or the decaying pulse of the liver is like a thin thread on the verge of breaking, or like a tightly wound wire about to snap. The patient will die within eighteen days. If the decaying pulse of the heart is like a thin fragile thread, the patient will surely die within nine days. If this pulse is found in the lung pulse, the patient will not survive longer than twelve days. If it is found in the kidney pulse, the patient will die in seven days. If it is found in the spleen pulse, the patient will die in four days.

A more complete prognosis involves coupling the information about the pulse with the examination of the facial color and the "spirit" expressed by the facial expressions (especially the eyes). In the Neijing, it is said that: "In diagnosis, observation of the spirit and facial color, and palpation of the pulses, are the two methods that were emphasized by the ancient emperors and revered teachers...." As a text expounding on the virtues of the ancient teachers, there were complaints about failings of the modern practitioners in their diagnostic work, which echoes forward to the modern era. The practitioners of the time were encouraged not to forget the other necessary diagnostic methods, especially inquiry:

Today, doctors deviate from [the treatment methods of ancient times]. They cannot even follow the changes in the four seasons [that influence the pulse and other body conditions]. They do not know the importance and principles of the complexion and pulses....Doctors today should eliminate their bad habits and ignorance, open their minds, and learn the essence of pulse and color diagnosis [i.e., analysis of facial colors]. Only by doing so will they ever succeed in reaching the level of the ancient sages....There is one other important thing. That is the interrogation of the patient, the inquiry....Select a quiet environment; close all doors and windows; gain the trust of your patient so that the patient can completely convey everything that is pertinent to the condition. Be thorough and differentiate the truth.

In the Huangdi Neijing (3), the pulse is mentioned briefly and simply among a list of symptoms that would indicate a particular disease stage or category; thus, for the taiyang disease, the pulse is floating, for a yangming disease, the pulse is large, and for the jueyin disease, the pulse is feeble. In the companion volume Jingui Yaolue, there is more description of the pulses and some explanation of their meaning. For example, it is said that:

A pulse too strong or too weak denotes illness. A minute pulse on the cun site and a chordal pulse on the chi site portends thoracic debility and aching because it reflects an extremely weak condition of yang in the upper warmer. Heart pain follows the thriving yin evil as characterized by the deep chordal pulse.

The presentation of diagnostic information in these works of Zhang Zhongjing confirms the importance of inquiry, since it is by this means that one learns the essential features described throughout most of the text, such as location of pain, duration of disease, and other factors that determine the selection of herbs (thirst, mental conditions, urination, etc.). In his preface to the Huangdi Neijing, Zhang continues the complaint expressed in the Neijing about practitioners in his time, a century or more after the Neijing was produced in the form we have currently:

Physicians today do not thoroughly study the medical classics before they begin to practice, but merely follow their predecessors with no attempt to improve age-old forms....They take the front pulse, but not the rear; check the hands, but not the feet; and do not make a diagnosis of the complete upper, middle, and lower parts of the body. How can a pulse alone and careless observation tell about all the syndromes and diseases?

The concern is about incomplete and careless diagnosis, particularly where the pulse is the primary diagnostic method (omitting or minimizing the others), and failure to carry out the full pulse taking (front and rear pulses). This is a theme that persists throughout Chinese medical history, and applies to modern medical diagnostics as well (where medical doctors are chided for having missed a diagnosis by not performing all necessary tests or by carelessly interpreting the test results). The proclaimed failings in the Han Dynasty times, an era regarded by subsequent authors as one of the high points of Chinese medicine, illustrate that the reverence for the past is aimed at the wise instructions of the small number of highly accomplished scholar physicians (who left behind the classic texts), rather than the state of medical practice as a whole. The desire, which can only be professed and never fully accomplished, is that all physicians should attain the highest possible standard and should master the diagnostic methods through diligent study of the classics and continual attention to detail.

THE PULSE CLASSIC

The subject of pulse diagnosis was first tackled in an organized manner by Wang Shuhe, who lived during the 3rd century A.D. (just after the fall of the Han Dynasty). Wang was responsible for recovering and organizing the Huangdi Neijing (see: A modern view of the Huangdi Neijing); he may have fully rewritten the first three critical chapters. His text on pulse diagnosis became known as the Mai Jing (Pulse Classic). Although the text had been regarded as quite difficult to understand, and was therefore often replaced by simpler, derivative tracts, it has, in modern times, been deemed a classic worthy of preservation. A translation of the Mai Jing, based on a modern Chinese edited version, has been published by Blue Poppy Press (4).

In the Mai Jing, a broad spectrum of applications for pulse diagnosis is delineated, including etiology of disease, nature of the disease, and prognosis. As an example of etiology and disease development, it is said that: "If the pulse is bowstring, tight, choppy, slippery, floating, or deep, these six point to murderous evils which are capable of causing disease in various channels." As an example of disease analysis, the following pulse characteristics and implications are given:

If its emerging and submerging are equal, this is a normal state; if its submerging is twice as long as its emerging, this is shaoyin. If its submerging is three time as long as its emerging, this is taiyin. If its submerging is four times as long as its emerging, this is jueyin. If its emerging is twice as long as its submerging, this is shaoyang. If its emerging is three times as long as submerging, this is yangming. If its emerging is four times as long as its submerging, this is taiyang.

As to prognosis, an example with great specificity is: "If, on the seventh or eighth day, a febrile disease exhibits a pulse which is not grasping-like but beating rapidly at a constant pace, there ought to arise a disease of loss of voice. Perspiration is expected to come in three days. If it fails to come then, death will occur on the fourth day." As before, the main prognostic value of the pulse was in relation to impending death (or, if the pulse is favorable, recovery from the disease).

After the production of the Mai Jing, many different conceptions of pulse diagnosis arose and led to a great deal of confusion about interpreting what was being felt by the physician. Xu Dachun (1693-1771) produced a chapter on the Mai Jing in his book Yixue Yuanliu Lun (12), commenting that:

Those experts who discussed the pulse through the ages have all contradicted one another, and they all differed in what they considered right and wrong. They all cling to their specific doctrine, and their advantages and errors balance each other....Students reading the Mai Jing must consult the Nei Jing, the Nan Jing, and the doctrines of Zhang Zhongjing [Huangdi Neijing, Jingui Yaolue].

In other words, the classic texts of the Han Dynasty have the basic doctrines of importance, and they must all be studied in order for the Mai Jing to be fully meaningful. The digressions in the theory and practice of pulse diagnosis that were made later should, according to Xu, be ignored, because they introduce confusion rather than clarification. All the books mentioned by Xu in the above quote are now available in English translation (see: Some selected Chinese medical texts in translation), reflecting the common view that they are essential to the study of Chinese medical doctrines.

AIM AND METHOD OF PULSE DIAGNOSIS

The aim of pulse diagnosis, like the other methods of diagnosis, has always been to obtain useful information about what goes on inside the body, what has caused disease, what might be done to rectify the problem, and what are the chances of success. According to the Chinese understanding, the pulse can reveal whether a syndrome is of hot or cold nature, whether it is of excess or deficiency type, which of the humors (qi, moisture, blood) are affected, and which organ systems suffer from dysfunction. In order to make these determinations, the physician must feel the pulse under the proper conditions-following the established procedures-and must then translate the unique pulse that is felt into one or more of the categories of pulse form.

In his book reviewing pulse diagnosis (5), Bob Flaws emphasizes the importance of learning the basic pulse categories in order for pulse diagnosis to be conducted effectively. He says:

In my experience, the secret of Chinese pulse examination is exactly this: One cannot feel a pulse image unless one can consciously and accurately state the standard, textbook definition of that pulse image.

In support of this contention, he also quotes Manfred Porkert (6):

This, precisely, is the critical issue: there is no point in attempting practical training in pulse diagnosis unless all pertinent theory and, more important, the complete iconography [set of image categories] of the pulse has previously been absorbed intellectually.

Chinese medical texts do not describe what the practitioner experience is (or should be) during pulse diagnosis; this is left to be passed on from accomplished practitioner to student. In contrast, these Western scholars are trying to relate to their Western readers, in written form, the steps by which one can master the diagnostic method. The basic premise outlined by Flaws and Porkert-that one must master the categories first-appears to be supported in the Chinese literature by the almost universal practice of introducing pulse diagnosis by listing and describing the basic set of pulse categories.

The most standard inconography involves from 24-28 different pulse forms, depending on the recitation (sometimes a pulse type is subdivided into two; sometimes a complex pulse type is not included), though simplified sets are often given in less formal presentations. Despite the numerous descriptions of pulse forms in the lengthy Mai Jing, the practitioner is really being asked to become familiar with this modest sized and basic set of pulse categories, which were first outlined in the opening chapter of the Mai Jing. In the English language translation of the book, the description of these fundamental pulse categories take up just 3 pages out of 360.

PULSE CATEGORIES

In a recent article describing the standard pulse categories by terminology expert Xie Zhufan (7), 26 basic pulse types were outlined and given updated English language interpretations (two of the types have the same Chinese name but different descriptions). Table 1 presents these pulse categories.

In the table, the English translation term is given first; in a few cases, alternative English names are given for the same traditional category indicated by a single Chinese term (given in pinyin). The naming and interpretation of the pulse is taken directly from the article Selected terms in traditional Chinese medicine and their interpretations (7). The comments are added here by the current author, with reference also to information from the Dictionary of Traditional Chinese Medicine (8). The 7 pulses presented first (scattered, intermittent, swift, hollow, faint, surging, and hidden) are ones that may have little relevance to practice of traditional medicine in the modern setting. The other 19 pulses appear more likely to help the practitioner determine imbalances that relate to the selection of traditional style therapeutics (i.e., acupuncture points and individual herbs). Several of the pulses listed in the table represent pairs depicting yin/yang opposites, such as: floating vs. sinking (surface/interior); slow vs. rapid (cold/hot); weak vs. replete (deficiency/excess); and short vs. long (also indicating deficiency/excess).

There are three additional pulse types reported in the Dictionary (8): gemai (hard and hollow pulse), is large and taut yet feels hollow like touching the surface of a drum, indicating loss of blood and essence; it may also occur with hypertension; laomai (a forceful and taut pulse) is felt only by hard pressure, usually seen in cases with accumulation of cold pathogenic factors yielding formation of a firm mass; and damai (large pulse), is a high pulse wave that lifts the finger to a greater height then normal. Damai is either forceful (has a large mass behind it, indicating excess heat with damaged internal organ function) or weak (indicating little force, seen in cases of general debility, with "floating yang"). Many authors regard these pulses as composites of two or more basic pulses rather than unique pulse types.

Table 1: Pulse Categories in Translation.

| Pulse Type | Interpretation | Comments |

| Scattered pulse [sanmai] | An irregular pulse, hardly perceptible, occurring in critical cases showing exhaustion of qi. | These are cases where the patient is critically ill, perhaps near death; such patients are normally hospitalized (or sent home to die) and their diagnosis is usually well-established. The pulse only tells that the patient is severely debilitated; it diffuses on light touch and is faint with heavy pressure. |

| Intermittent pulse [daimai] | A slow pulse pausing at regular intervals, often occurring in exhaustion of zangfu organs, severe trauma, or being seized by terror. | As with the scattered pulse, this pulse type is usually only seen in cases where the person is hospitalized or otherwise in an advanced disease stage. It is expected to occur, for example, with those having serious heart disease. |

| Swift pulse [jimai] | A pulse feeling hasty and swift, 120-140 beats per minute, often occurring in severe acute febrile disease or consumptive conditions. | This pulse is so rapid (twice the normal speed) that it is easily detected; the acute febrile disease involves an easily measured high temperature and is usually subject of pathogen testing. Consumptive conditions with such high pulse rates are generally under emergency medical care. |

| Hollow pulse [koumai] | A pulse that feels floating, large, soft, and hollow, like a scallion stalk, occurring in massive loss of blood. | Massive blood loss can easily be reported. This pulse is felt lightly at the superficial level and lightly at the deep level, but barely felt at the intermediate level. The light pulse is like the flexible scallion material, with a hollow center. It means that there is still some flow of qi at the vessel surface, but not much blood. |

| Faint pulse [weimai] | A pulse feeling thready and soft, scarcely perceptible, showing extreme exhaustion. | Extreme exhaustion is obvious to both the patient and the practitioner. The pulse, lacking substance, volume, and strength, simply reveals the exhaustion of the body essences. It is weaker than the thready (faint) pulse. |

| Surging pulse [hongmai] | A pulse beating like dashing waves with forceful rising and gradual decline, indicating excessive heat. | Excess heat syndromes are rarely difficult to detect, so this pulse type adds little information. The force of the pulse indicates that the condition is pathologically excessive, the gradual decline shows that the syndrome is primarily one of heat (qi excess) rather than fluid excess. The pulse is sometimes described as a "full pulse" indicating the excess condition. |

| Hidden pulse [fumai] | A pulse that can only be felt by pressing to the bone, located even deeper than the sinking pulse, often appearing in syncope or severe pain. | This pulse is quite extreme, in that one can barely detect it except by applying deep pressure; it gives the sense that the pulse is hidden in the muscles. If there is little musculature, it is as if it is resting on the surface of the bone. The conditions for which it is typical, syncome (fainting) and severe pain, can easily be determined without taking the pulse. |

| Knotted pulse [jiemai] | A slow pulse pausing at irregular intervals, often occurring in stagnation of qi and blood. | Qi and blood stasis represents a traditional diagnostic category that does not have a direct correlation with modern diagnostics. In this pulse, the irregularity and slowness is due to obstruction. |

| Hurried pulse [cumai] | A rapid pulse with irregular intermittence, often due to excessive heat with stagnation of qi and blood, or retention of phlegm or undigested food. | This is the excess version of the knotted pulse. It is sometimes called the "running" or "abrupt" pulse. The rapidity indicates heat and the irregularity indicates the blockage caused by stagnation and/or accumulation. |

| Long pulse [changmai] | A pulse with lengthy extent and prolonged stroke. A long pulse with moderate tension may be found in normal persons, but a long and stringy pulse indicates excess of yang, especially liver yang. | Particularly in young people, the pulse is felt rather easily across all three finger positions, as is characteristic of the long pulse. The prolonged stroke shows that the vessels are both strong and flexible. A stringy quality indicates a certain level of tension, that corresponds with a liver syndrome. In cases of acute disease, a long pulse will occur when there is a strong confrontation between the body's resistance and the pathogenic factor. |

| Short pulse [duanmai] | A pulse with short extent. A short and forceful pulse is often found in qi stagnation and a short and weak pulse implies consumption of qi. | The short pulse seems to deteriorate from the central pulse position towards the two adjacent pulse positions. It strikes the middle finger sharply and leaves quickly. On the one hand, this can represent contraction of the qi, as in liver qi stagnation, or it can represent deficiency of the qi. |

| Fine pulse [ximai] or Thready pulse [ximai] | A pulse felt like a fine thread, but always distinctly perceptible, indicating deficiency of qi and blood or other deficiency states. | Although the deficiency can be easily detected by other means, some patients can show an artificially robust exterior appearance, while having notable deficiency. Essence deficiency, the result of chronic illness, can give rise to this pulse type. |

| Hesitant pulse [semai] or Uneven pulse [semai] or Choppy pulse [semai] | A pulse coming and going choppily with small, fine, slow, joggling tempo like scraping bamboo with a knife, indicating sluggish blood circulation due to deficiency of blood or stagnation of qi and blood. | This has a more irregular pattern than the knotted pulse that also shows stagnation of qi and blood. The severity of the blood disorder is greater. As the knife scrapes across the bamboo, it vibrates and irregularly moves forward, yielding a choppy sensation with brief hesitations or interruptions in movement. |

| Slippery pulse [huamai] | A pulse like beads rolling on a plate, found in patients with phlegm-damp or food stagnation, and also in normal persons. A slippery and rapid pulse may indicate pregnancy. | While use of the pulse to indicate pregnancy is no longer of value (as more reliable tests are readily available), and while this pulse, like the long pulse is often normal (occurring especially in persons who are somewhat heavy), it is a good confirmation of a diagnosis of phlegm-damp accumulation. It is sometimes referred to as a "smooth pulse." |

| Relaxed pulse [huanmai] or Loose pulse [huanmai] | A pulse with diminished tension, occurring in dampness or insufficiency of the spleen. | The pulse has a softness or looseness that is due to the weakness of the qi and the obstructing effect of dampness. The dampness differs from phlegm-damp in having no solidity. |

| Moderate pulse [huanmai] | A pulse with even rhythm and moderate tension, indicating a normal condition. | This is similar to the loose pulse, above (and the Chinese name is the same), except that it has a better tension, showing that the qi is adequate. As a normal pulse, it indicates that the disease condition being treated is localized and has not disturbed or been caused by disturbance of the viscera. |

| Tense pulse [jinmai] or Tight pulse [jinmai] | A pulse felt like a tightly stretched cord, indicating cold or pain. | This is similar to the wiry pulse, but not as long. While pain can be easily reported, a cold syndrome is sometimes disguised by localized heat symptoms; this pulse can indicate either exterior or interior chill. |

| Stringy pulse [xianmai] or Wiry pulse [xianmai] | A pulse that feels straight and long, like a musical instrument string, usually occurring in liver and gallbladder disorders or severe pain. | This is similar to the tense pulse, but longer and more tremulous. While severe pain can be easily reported, the wiry pulse confirms the liver and/or gallbladder as the focal point of the internal disharmony. |

| Replete pulse [shimai] or Forceful pulse [shimai] | A pulse felt vigorously and forcefully on both light and heavy pressure, implying excessiveness. | This pulse gives relatively little information other than that the condition is one of excess; one must further determine the nature of the excess in order to select a therapeutic strategy. This pulse, however, generally rejects the use of tonification strategies, as it indicates that the body resistance is undamaged. |

| Weak pulse [ruomai] | A pulse feeling deep and soft, usually due to deficiency of qi and blood. | This pulse is similar to the fine pulse, but has a softer quality. Usually, this indicates a weakness of the spleen qi, leading to deficiency of both qi and blood. In the system of pulse taking, it serves as the opposite of the replete pulse. |

| Soggy pulse [rumai] | A superficial, thin, and soft pulse which can be felt on light touch like a thread floating on water, but grows faint on hard pressuring, indicating deficiency conditions or damp retention. | This pulse is similar to the fine and weak pulses. The thready pulse sensation felt on light touch gives the impression of being easily moved, as if floating on water; hence, it tends to indicate spleen-qi deficiency with accumulation of dampness. It is sometimes referred to as the "soft pulse." |

| Feeble pulse [xumai] | A pulse feeling feeble and void, indicating deficiency of qi and blood or impairment of body fluid. | This pulse is similar to the weak, fine, and faint pulses. It occurs when the deficiency of blood is more severe than in the case of weak and fine pulses, but not so deficient as with the faint pulse. |

| Rapid pulse [shoumai] | A pulse with increased frequency (more than 90 beats per minute), usually indicating the presence of heat. | The rapid pulse is quite a bit more rapid than a normal pulse, and usually occurs only when there is a serious illness and mainly when there is a fever. The pulse can become rapid from activity prior to pulse taking. |

| Slow pulse [chimai] | A pulse with reduced frequency (less than 60 beats per minute), usually indicating endogenous cold. | A slow pulse may also indicate a person at rest who normally has a high level of physical activity, so must be interpreted in light of other diagnostic information. |

| Sinking pulse [chenmai] | A pulse that can only be felt by pressing hard, usually indicating that the illness is located deep in the interior of the body. | The circulation of qi and blood from the internal viscera to the surface is weak; it is usually confined to the interior as part of the body's attempt to deal with a serious disorder threatening the viscera. Sometimes referred to as the deep pulse. |

| Floating pulse [fumai] | A pulse that is palpable by light touch and grows faint on hard pressure, usually indicating that the illness is in the exterior portion of the body. | The circulation of qi and blood is focused in the body's surface to deal with an external pathogenic agent. The internal circulation is temporarily sacrificed to assure that the pathogen is eliminated before it can enter more deeply and cause serious problems at the visceral level. Debilitated patients may show a floating pulse that is feeble, indicating the inability to retain the qi and yang in the interior due to the deficiency of the vital organs. |

Gao De, a diagnosis specialist at the Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, cautioned that pulse taking has become obscured by a multiplication of pulse categories (13). He wrote:

The types of pulses that have been listed are too numerous and great disparity exists in the ways in which they have been recorded. Beginners often find them confusing. There are two major reasons for such confusion:

- The difference between some categories is not so sharp, such as that between overflowing and large, thready and small, rapid and fast (hurried), and deep and hidden.

- Additional nomenclature is given to the multi-feature pulse conditions. For example, the leathery pulse is the combination of hollow and wiry; weak-superficial is another name for both weak and superficial; firm (or hard) means the combination of deep, full, wiry, and long; etc.

Single-feature pulse conditions are already numerous enough and the additional nomenclature adds even more names which have little clinical significance but add to the difficulties for beginners. Therefore, it is advisable to simplify the categories of pulse conditions by omitting the names of those confusing multi-feature pulse conditions. If more than one feature has to be described, the doctor can simply put those single features together. With this in mind, I would recommend the following list of simplified pulse conditions:

superficial vs. deep;

slow vs. rapid;

empty vs. full;

overflowing vs. thready; and

minute, rolling, choppy, wiry, scattered, hasty, knotted, and intermittent.

superficial vs. deep;

slow vs. rapid;

empty vs. full;

overflowing vs. thready; and

minute, rolling, choppy, wiry, scattered, hasty, knotted, and intermittent.

Mastery of these 16 basic single-feature pulse conditions, together with their possible combinations and their indications, is sufficient to meet the needs in clinical differentiation of syndromes.

In the text Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (15), there is a listing of 17 pulses to know, all of which are said to represent the abnormal conditions. The same paired pulses as listed above by Gao De are included, but the list of additional pulses varies slightly. Compared to the list of 28 pulses in Table 1, the categories that have been disregarded in order to yield the shorter list of abnormal pulses include several of those that are indicating severe deficiency diseases (scattered, hollow, faint) and those that indicate a relatively normal condition (long, relaxed, moderate). In Essentials of Chinese Acupuncture (20), 12 basic pulses are listed, with the same paired pulses given above, plus the wiry pulse and three of the irregular pulses.

Similarly, in the book Chinese Herbal Science (17) by Hong-yen Hsu, the pulses of importance are limited in number. The author states: "In traditional Chinese pulse diagnosis, there are 28 qualities, but they are grouping into eight types according to the nature and associated symptoms. The most important qualities for the physician to be able to differentiation are floating, sinking, slow, and fast." The other four pulse qualities listed in this text are: weak, solid, slippery, and full. The same author gave a more detailed listing of pulses in a presentation on Chinese diagnostics (18), with 7 types of floating pulses, 3 types of sinking pulses, 5 types of late pulses, 5 types of fast pulses, 6 types of weak pulses, 3 types of solid pulses, and 11 types of dying pulses. Thus, 40 pulse types were depicted, but they fell into just a few basic categories.

The general implication of the literature on pulse is that there are about two dozen pulse types to be learned in detail, but that there are only a few of them (sometimes grouping similar pulses together) that are critical for the everyday utilization of this diagnostic technique used in combination with other methods of diagnosis. Therefore, pulse diagnosis should be within the grasp of all practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine. Those who have limited training and abilities must learn about 8-17 fundamental pulse types; those who wish to make greater use of this technique must be able to distinguish more subtle variations, but the number of different pulses to learn is still limited.

TRADITIONAL PULSE TAKING METHODS

A variety of sites for pulse taking have been mentioned in the traditional literature. For example, in the Neijing Suwen, it is mentioned that the yang pulses can be felt at the carotid artery (next to the Adam's apple on the neck), while the yin pulses can be felt at the radial artery (above the wrist). Under healthy circumstances these pulses should be the same, but they differ with disease. Feeling the pulse at more than one site is said to improve the diagnosis. Other pulse taking methods include using the head and upper and lower limbs, and use of different pulse locations at arteries under certain acupuncture points to assess individual organs (e.g, at taiyang, ermen, dicang, daying, shenmen, hegu, wuli, taichong, qimen, chongyang, and taixi).

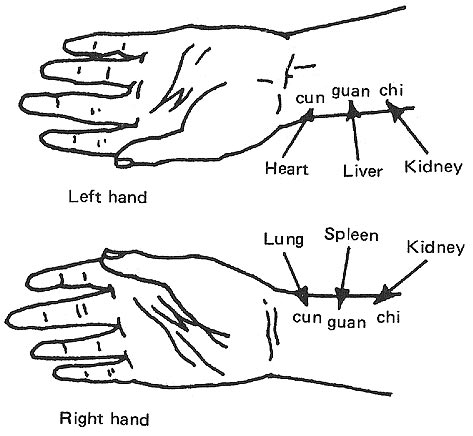

Despite the availability of more than one site for pulse taking, standard Chinese medical diagnosis almost always is limited to the wrist pulse. It is felt by placing three fingers at the radial artery (see Figures 1 & 2), testing each arm one at a time. The classic Chinese pattern of pulse taking is based on touching the wrist with three levels of pressure: superficial palpation (almost no pressure, to feel the bounding of the pulse up to the skin surface); intermediate palpation (light pressure, to feel the basic pulse form); and deep palpation (somewhat heavy pressure, to feel how the pulse is able to emerge from the physical constraint). In addition, the changes in pulse feeling as one moves from less to more pressure, and again from more to less pressure, can also give some information about the resilience of the pulse. In essence, there are nine pulse takings on each wrist: one for each of the three pulse taking fingers at each of the three levels of pressure. However, the system of pulse taking can be divided into two parts:

- The general sensation of the pulse at the two wrists overall: instead of distinguishing each pulse position (cun, guan, chi), the quality of the pulse is categorized generally, as felt under the three fingers. In this case, there are just three pulse readings at each wrist, with superficial, intermediate, and deep pressure. The results of this type of pulse reading are then categorized as in Table 1, with combinations of two (or infrequently more than two) pulse categories being possible.

- Feeling the pulse at each of the individual positions on the wrists, to assess the condition of each of the internal organs. The association of individual pulse positions with internal organs has changed over time and varies from one traditional system to another (illustrating a lack of consistency in interpretation). The current understanding is that the left wrist presents information for the heart, liver, and kidney yin, while the right wrist presents information for the lung, spleen, and kidney yang. This classification is consistent with the five element system that depicts five basic viscera; the kidney is subdivided to make the sixth. However, one can alternatively incorporate the pericardium/triple burner system in place of the kidney yang pulse.

The interpretation of which pulse position corresponds to which organ has changed over time; the assignments commonly relied upon today are attributed to Li Shizhen (1518-1593), who is most famous as the author of the Bencao Gangmu. He wrote Binhu Maixue (The Pulse Studies of Binhu), in which the pulse taking method was elaborated, for which 27 categories of pulse were listed.

The various outcomes of the pulse diagnostics are outlined succinctly and in table form in Ted Kaptchuk's book The Web that Has No Weaver (14). Here is an example for one pulse type, the choppy pulse:

- Combination pulses: choppy and wiry indicates constraining liver qi, congealed blood; choppy and frail indicates qi exhausted; choppy and minute indicates deficient blood and deficient yang; choppy and thin indicates dried fluids.

- Pulses by position: first position pulse being choppy indicates deficient heart qi and chest pain; if only on the left side, heart pain and heart palpitations; if on the right side, deficient lung qi, cough with foamy sputum; second position pulse being choppy indicates deficient spleen qi and deficient stomach qi, painful, distended flanks; if just the left side, it means deficient liver blood; on the right side it means weak spleen and inability to eat; third position pulse being choppy indicates essence and blood are injured; constipation or dribbling urine, or bleeding from the anus; if just on the left side, it means lower back is weak and sore; if just on the right side, it means a weak mingmen fire and/or essence injury.

FACTORS TO CONSIDER BEFORE AND DURING PULSE EXAMINATION

In the well-known study guide, Acupuncture: A Comprehensive Text (15), it is said that: "Diagnosis by pulse is a subtle art and, even more than other diagnostic procedures, requires a tremendous amount of attentiveness and experience in order to acquire the sensitivity necessary to do it well." Proper pulse taking involves accounting for a number of factors that can affect the ability to feel the pulse and interpret it properly. These factors include several that affect the traditional practitioner in China, but some that present new problems for the modern practitioner:

- The patient must be relaxed and have not undertaken any vigorous activity for some time prior to the pulse taking. It is generally thought that the pulse should be felt in the morning to get the best reading. Unfortunately, most modern patients rush through traffic to arrive at an appointment that takes place later in the day, after many activities have influenced the quality of the pulse.

- The patient's arm, wrist, and hand must be relaxed, with the hand supported on a small pillow or other object; the hand is below the heart, at about the location of the navel as the person sits. The physician is calm and able to concentrate; the physician's hand that is performing the diagnosis is also in a relaxed position. As described in Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion: "The three fingers are slightly flexed, presenting the shape of an arch. The finger tips are kept on the same horizontal level." In many rushed modern practices, the pulse is taken whenever it seems convenient, with the position of patient and practitioner often being less than ideal, thus distorting the pulse reading.

- The placement of the physician's fingers are at the cun ("inch"), guan ("bar"), and chi ("cubit") positions. The middle finger is placed over the eminent head of the radius and the other two fingers are placed adjacent to that one, but usually not touching one another or just barely touching (the separation of fingers depends on the size of the patient, being greater in those who are tall and have long arms, and less in patients who are relatively smaller), along the artery. The wide range of body types that are encountered in the modern practice make it more difficult to place the fingers properly to feel the pulse.

- The physician, through training and experience, applies the appropriate amount of pressure. Gao De, in his review of pulse diagnosis, commented: "Doctors exerting different forces in pulse-taking get different conclusions regarding both the depth at which the pulse beating is felt and the strength of the pulse; hence, also different conclusions of the overall pulse condition arise." Having applied pressure properly, the doctor must be familiar with the different categories of pulse conditions so as to be able to classify that which is detected into the category that most closely describes what is felt. As described above, this is the essential feature of pulse taking, one that Western writers must emphasize because it is not necessarily taught that way in the standard training programs.

- Adequate duration of pulse diagnosis is allowed to assure that the pulse description holds true over many pulsations, and that both arms are checked in order to give a full evaluation. Often, there is not enough time available to perform a complete pulse diagnosis. As stated in Acupuncture: A Comprehensive Text: "The doctor must refrain from quick pulse-taking in a hurried frame of mind. If this precaution is not observed, the resulting pulse readings will be misleading."

- One must take into account the season. Although there is great detail in describing seasonal influences on the pulse in traditional texts, a most general depiction is: the spring pulse is slightly taut (bowstring); the summer pulse is slightly full and surging; the autumn pulse somewhat floating and fine or soft; and the winter pulse somewhat sinking and slippery or hard. If the pulse type is consistent with the season, that indicates a normal condition, while if it differs markedly, it suggests a pathological condition. There is some question, however, as to how this seasonal influence might be modified by modern living habits, including rising and going to bed out of synch with the sunrise and sunset, use of central heating and air conditioning, and eating foods out of season.

- One must take into account patient characteristics that influence the pulse. According to Acupuncture: A Comprehensive Text: In a healthy person, the front position tends to be floating, while the rear position is usually submerged....Athletes often have a slow pulse, young children have quick pulses. Fat people have deep pulses, while thin people have pulses with a tendency to be bigger than normal. Woman's pulses are usually softer and slightly quicker than men's. Also, women's right pulses are usually stronger than their left, while the opposite is true of men.Gao De commented:A doctor must be aware of the fact that as numerous changes can take place within a man's body under natural physical condition, so can variations of normal pulse condition. Such variations will be within certain limits and still bear the basic features of the normal pulse condition. Theoretically speaking, the demarcation line between variation of normal pulse condition and diseased pulse condition is not clear cut....Diseases pulse conditions: 1) are attended with symptoms and signs corresponding to the pulse conditions; 2. cannot be explained by the external factors that may affect pulse condition [e.g., age, sex, physical constitution, season, etc.]; and 3) remain abnormal after the external factors seemingly affecting the pulse are removed unless effective treatment is applied.In addition to these factors based on traditional and natural considerations, one must take into account new factors that may influence the pulse, such as use of drugs, including nicotine products, pharmaceutical drugs, and illegal drugs.

The numerous factors to be taken into consideration and the associated difficulties in interpretation mean that pulse taking in the modern setting is rarely as informative as it is depicted in the historical texts. Nonetheless, despite the problems that can arise, modern pulse taking can usually reveal most of the 24-28 basic categories. The pulse taking may not as easily reveal the more numerous indications depicted in the Mai Jing or in some other texts. Of course, a practitioner who specializes in pulse diagnosis and spends years studying the theory and categories and carefully takes the pulse of many hundreds of patients could still master the system, but the impetus to do so seems muted: there are too many interferences of modern society that make the pulse less informative and there is plenty of other diagnostic information available. Yet, those involved with modern Chinese medicine should not dismiss the pulse simply because a variety of factors need to be taken into account; it becomes necessary to become aware of these factors and give adequate time and attention so as to limit their potential for confusing the interpretation.

PULSE AS AN AID TO OTHER DIAGNOSTICS

During the development of Chinese medicine, there appears to have arisen, from time to time, an understanding that a well-trained physician was able to make a diagnosis almost entirely by pulse taking, while asking virtually no questions of the patient. As a result, pulse analysis sometimes took on a certain mystical aura and was a major focus of doctor-patient interaction. Aside from the complaints about this in the historical literature as already cited, Gao De mentions it as a continuing problem in the practice of Chinese medicine up to the modern era: "Some even applied pulse diagnosis in clinical practice in a completely isolated way, disregarding the other three, namely inspection, smelling, and asking, thus having led the development of pulse diagnosis astray." In Acupuncture: A Comprehensive Text, the authors still allude to the possibility of using the pulse as a sole method of diagnosis by saying: "While most Chinese doctors would agree that the pulse is best used in conjunction with the other diagnostic methods, doctors well-skilled in pulse diagnosis can discover an enormous amount of information about their patients by this method alone."

The utility of pulse diagnosis may be more properly viewed as belonging to the realm of confirming a diagnosis attained by other means, including modern medical testing, or implying that something is missing from the diagnosis when the pulse does not agree, setting off a series of questions or investigations for additional information. This application of pulse as confirmation is one that Bob Flaws has argued against having modern practitioners rely on, even though he observed it as a common situation in China. He wrote in the introduction to his book on pulse:

This Western ambivalence toward and pervasive lack of mastery of the pulse examination is, I believe, exacerbated by a somewhat similar attitude towards pulse examination current in the People's Republic of China at least in the 1980's. When I was a student in China during that time, the importance of pulse examination was deliberately played down by many of my teachers and clinical preceptors....I never had a teacher tell me a pulse was anything other than wiry, slippery, fast, slow, floating, deep, or fine...it seems that many modern Chinese TCM practitioners relegate pulse examination to a minor, confirmatory role....I believe that mastery of pulse examination is vitally important to making a correct TCM pattern discrimination. And, I believe the pulse examination is, perhaps, even more important to Western practitioners than for our Chinese counterparts.

Indeed, the set of pulses that Flaws mentioned hearing repeatedly in China is the most basic set that must be learned and is similar to what was described above by several authors as the key categories. He has relayed a group of opposing pairs that help assure that the treatment is consistent with the underlying pattern and unlikely to cause adverse effects by reinforcing an imbalance. In the opening chapter of The Heart Transmission of Medicine (9), by the famous 19th Century physician Liu Yiren, he states: "Four kinds of pulse are the key criteria in examination: the floating, deep, slow, and rapid. The floating and deep can be discerned by light and heavy pressure of the fingers. The slow and rapid may become the moderate and the racing. This can be identified by respirations [i.e., counting the number of pulses per respiration]." While Liu then goes on to give a somewhat more complex system of diagnosis, with attention focused on the three pulse positions of each radial artery to discover ailments of the major internal organs, even that is greatly simplified compared to what is found in the Mai Jing. Overall, Liu aims his comments on pulse at helping the practitioner to integrate pulse information with other diagnostic methods, mainly rational inquiry.

In his book, Flaws goes on to argue that the importance of the pulse in modern practice lies with the complexity of chronic conditions suffered by many patients who turn to acupuncture in the West. The idea is that these patients typically present a picture that is difficult to sort out, and that the pulse can provide information that resolves the dilemma. I would argue, contrarily, that this complexity of the patients makes pulse diagnosis more difficult to rely on, rather than more valuable. One can come to this view by reading the indications of the pulses in the Mai Jing, in which the interpretations are very succinct and focused: this pulse is common in the spring, this pulse means taiyin disease, this pulse means a fever, etc. By contrast, the complexity of modern patients, especially those who are older and suffer from numerous diseases, means that within one individual there is a complex of deficiencies and excesses, of internal and surface disorders, of stagnation and looseness, and influences of drugs, surgery, and daily habits that don't fit any traditional pattern. The resulting pulse is more difficult to analyze and less informative.

According to Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion: "As the process of disease is complex, the abnormal pulses do not often appear in their pure form, the combination of two pulses or more is often present. The condition of a number of pulses present at the same time is called complicated pulse. The indication of a complicated pulse is the combination of indications of each single pulse." The complexity depicted in this textbook statement is applied to ordinary cases that have occurred throughout medical history in China. Today, the influence of surgery, powerful modern drugs that are taken chronically, and extreme variability in life style means that the complexity can be even greater. Thus, the physician who wishes to rely on the pulse under such circumstances must become familiar not only with several basic pulse types, but must develop the ability to detect and interpret very complex pulse forms, teasing out multiple pulse types within the sensation under the fingers. Some physicians have argued, instead, that the pulse diagnosis should have a relatively limited role. Xu Dachun commented: "In my own view, the doctrine of the pulse only includes examining whether a patient's qi and blood are present abundantly or insufficiently, and through which meridian or through which organ cold, heat, or other evil influences flow. This has to be compared to the patient's symptoms...."

Clearly, the role of pulse within the full framework of diagnosis will remain an area of some contention. Advocates of pulse diagnosis having a central role can point to the large amount of information contained in the pulse that can lead one to an improved understanding of the disease process affecting the patient; critics will point to the wide variation in results of pulse taking, being dependent on so many factors, and will emphasize, instead, the essential role of examining the medical history and current symptoms as revealed by inquiry. However, few proponents of pulse diagnosis today would suggest downgrading the other diagnostic techniques and few critics of pulse diagnosis propose eliminating it. So, a certain level of consensus arises.

THE POTENTIAL ROLE OF PULSE DIAGNOSIS IN MODERN PRACTICE OF TCM

In modern medicine, the traditional style of pulse diagnosis, which was also practiced in a slightly different form in Western medicine until the 19th century, is replaced by a number of other tests. Tests by stethoscope and blood pressure cuff are routinely performed as pulse diagnostic techniques. The stethoscope reveals pulse rate and, at a low level of inference, irregularities in the structure and function of the heart, which must be evaluated further. When deemed necessary, additional testing is performed via various heart monitors, such as an electrocardiogram. The non-invasive sonograms as well as the more invasive testing (e.g., insertion of monitors into the body) allow modern physicians to examine the interior of the arteries and the heart. The information from these tests is generally understood to reflect only the conditions of the heart and major vessels (the cardiovascular system); it is not thought of as a means of examining other aspects of health. Unlike the traditional concept, the pulse form or information obtained by examining the vessels is not thought to provide useful information about, for example, the liver, kidney, lung, or spleen conditions.

Modern medicine has numerous other kinds of tests, including blood tests, urine tests, and a variety of scans and biopsies, that reveal a tremendous amount of information about what goes on inside the body, so as to produce a diagnosis. Such tests reveal much about the functions of the internal organs; for example, inflammation of the liver or malfunction of the kidney filtration system is readily detected with a simple blood test. Most of these testing methods have been utilized only in recent decades and add a new dimension to the practice of Chinese medicine.

While patients in China have come to rely on the traditional medical practitioners to simply carry out their diagnosis in silence and prescribe a therapy to be taken without question, modern patients in the West prefer to talk about their diseases. They usually demand to have explanations given for every step of diagnosis and for every factor that goes into a determination of a therapy. In fact, one of the main complaints raised by Westerners who visit Chinese immigrant doctors is that there is no significant discussion of their case, even when language is not a major barrier. For the Western patient, the focus is shifted towards the concerns that can be verbally expressed and away from the more mysterious diagnosis attained by pulse taking.

The complex condition of many modern patients may require one to rely heavily on modern medical diagnostics as a primary resource, making it the essential fifth diagnostic method for the practitioner of Chinese medicine. This is not a matter of the traditional practitioner deciding that this is the desired route, but a reflection of the extent to which modern lifestyle and modern medicine imposes itself on people who might have an interest in a traditional and natural approach. It is not uncommon for a patient to come to a traditional practitioner with Western medical test results and diagnosis and to want to know what is going to be done specifically about this situation as defined by those tests. A response that the therapy will rectify qi and blood and resolve the dysfunction of an organ system not mentioned in the modern test results may prove unsatisfying to the patient. Yet, it is precisely in this area-of measuring traditional-style indicators-that pulse diagnosis is employed in order to make corrections.

The question arises: does the old system of pulse diagnosis still have a value to practitioners of traditional medicine given the wealth of information derived from modern tests? In particular, in Western countries where extensive testing is readily available, can the traditional practitioner either ignore the information from those tests in favor of traditional style diagnostic methods or even gain any additional information from traditional pulse diagnosis once the modern tests have been conducted? This is answered in favor of retaining pulse diagnosis because of the nature of the therapeutics to be employed by the traditional practitioner. For the most part, the indications and applications of acupuncture and herbal therapies are not described in terms that correlate with the results of modern medical tests. They are described in terms of effects on qi and blood, hot and cold, and the zangfu organs. Even with the more limited use of pulse diagnosis that has been advocated by many authorities-relying on only about half of the basic pulse categories to get the fundamental differentiation-the results of the pulse taking can be applied to determining the therapeutic strategy. Regardless of whether one considers pulse taking a central and key part of a traditional style diagnosis or relegates it to a more minor confirmatory role, it still belongs to the modern practice of traditional medicine and requires the practitioner to be familiar with the major pulse categories.

ALTERED USE OF PULSE DIAGNOSIS

Many acupuncturists trained in the West have pursued a type of pulse diagnosis that is not described in the traditional Chinese literature. While the original Chinese pulse taking is utilized to arrive at both a diagnosis and at prognosis, many Western acupuncturists utilize a pulse analysis to determine whether or not they have properly inserted the needles. This is done by feeling the pulse after the needles have been inserted, either immediately or after they have been in place for several minutes. It is claimed that a properly conducted treatment yields correction of the pulse to a normal, or more normal, condition which is detected at the time of the treatment. Presumably, what is being detected is the improvement in the flow of qi and blood under the influence of the acupuncture needles.

The source of this method and application of pulse diagnosis remains unclear, but it was described by He Honlao, a Chinese acupuncturist working in the U.S., in an article published in 1987 (10). He stated: "By clinical practice, I noticed the fact: There are changes in the pulse condition after acupuncture." In explaining the observation, he conjectured that this use of the pulse analysis was a means of detecting the "arrival of qi" with acupuncture (see: Getting qi). From the modern perspective, he referred to research carried out in China during the 1950's that indicated a short term contraction followed by a longer-term expansion (dilation) of the blood vessels as a response to acupuncture therapy. In his article, he evaluated the pulse changes in 400 patients who had a string-like pulse (in which he included wiry, tense, solid, and firm pulse types), which indicated a tension syndrome. Accordingly, if acupuncture successfully dilates and relaxes the vessels, the pulse will change so that it is not as string-like (or taut). He claimed that in those patients whose pulse changed (softened immediately, as well as eventually, after several treatments) with acupuncture, nearly all had their symptoms relieved; of those whose pulse did not change with acupuncture, or those that showed immediate changes that promptly reverted after treatment, the symptoms were usually not relieved (in 3 out of 4 cases).

Dr. He indicated that, ideally, the pulse would return to normal or markedly calm down after the needle insertion and this improved pulse condition would continue until the needle was withdrawn; the pulse would stay calm at least for a time afterward. In some cases, the pulse returned to its former condition immediately after needle removal; and in other cases, the pulse was not altered by acupuncture at all. In rare cases, the pulse would actually become stronger, or more tense. He also noted that over several treatments the majority of patients had their pulse gradually becoming more normal, while others took several treatments before this response developed at all; some patients continually returned to pretreatment pulse conditions after every acupuncture session.

In the introduction to the article, Dr. He describes his observation as a "discovery," therefore not something belonging to the Chinese tradition and not something that he was aware was being relied upon by other acupuncturists at the time. In his discussion, he cites one statement from the Jingui Yaolue that he believes supports his contention and method. The quotation, taken here from a published translation (11), states: "If the pulse is minute and harsh on the cun site and thin and tense on the guan site, it is appropriate to activate yang qi by acupuncture in order to soften the harshness and to relax the tenseness, thus bringing about recovery." Dr. He has assumed, perhaps correctly, that the softening and relaxing effect described in this text applies to the immediate change in the described pulse, as opposed to merely suggesting a change in the patient's overall tense condition. It is difficult to know what was meant in the ancient text, but the lack of further reference to the spontaneous pulse changes in the traditional Chinese medical literature suggests that this was not a major means of utilizing pulse evaluation.

It would not be surprising that acupuncture would alter the pulse sensation detected in some or even most individuals (see: An introduction to acupuncture and how it works). More research would be needed to determine how widespread this phenomena is, since Dr. He described only one very broad type of pulse and did not indicate anything about the nature of the treatments given (for example, whether needles were inserted proximate to the artery on which the pulse was measured). Such research might help to confirm or deny whether such pulse changes were truly valuable indicators of the success of a long-term treatment. Certainly, this method has a potential for good use in the modern setting where some people are asked to pursue acupuncture for many sessions over several weeks in order to determine if it is ultimately going to alleviate their condition. The immediate pulse response or lack thereof, if truly informative as Dr. He suggests, might help the practitioner and patient determine the likelihood of success after only a couple of sessions.

While this type of diagnosis may be valuable for its primary purpose as a means of confirming the desired reaction from acupuncture therapy, it is not the same as the pulse taking method that is used for basic diagnosis and should not be assumed to replace the traditional style and application of pulse diagnosis. Rather, it can be regarded as an added technique which may be of value for the modern practitioner.

ATTEMPTS TO MAKE PULSE DIAGNOSIS OBJECTIVE

One of the serious objections to reliance on pulse diagnosis is that the pulse form determined by a practitioner is very subjective. It relies on how the physician places fingers on the wrist, what pressure is applied, and how the physician's mind interprets the sensations. Several physicians feeling the pulse of the same patient consecutively may report differing pulses. In China, researchers hoped to illustrate the value of the wrist pulses as a diagnostic method and also to aid in standardizing their measurement by devising modern devices for getting an objective pulse form. The result of such a measurement, using devices to detect the pulse, is a printed version, called a sphygmogram.

In his article on pulse diagnosis, Gao De said that: "The most pressing need in our study on pulse taking diagnosis is to devise an instrument to assist doctors when they take pulse with their fingers so as to get an objective judgment of the patient's pulse condition." Such instruments were soon developed. At a 1987 traditional medicine conference in Shanghai (19), several doctors reported on methods of measuring the pulse by pulse detecting devices. They further proposed that such measuring devices could assist students of Chinese medicine in learning pulse diagnosis, since the accuracy of the students' pulse determinations could be verified by the sphygmogram. Indeed, one author described the use of a device to reproduce the measured pulse which could then transmit the pulse to the student. By this means, the different kinds of pulses, having been prerecorded and stored in a computer, could be imitated for the student to experience so that each of the pulse categories could be learned. Just as simulators are used today to train pilots learning to fly, these pulse simulations are deemed a means of training practitioners to perform the diagnosis, which is to be mastered with actual pulse feeling after learning the basics. Fei Zhaofu and his colleagues at the Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine commented about the pulse-imitating devices used for this purpose:

Imitating the pulse actually means that the abstract descriptions and images [of the traditional system] are changed to specific figures signifying digital senses directly felt and stored. During the process of investigation, the device has been affirmed by many veteran practitioners of TCM, with repeated correction for improvement leading to its final approval by TCM circles. The device is therefore considered to have effectively inherited TCM sphygmology theory and preserved the pulse feeling experience of TCM. Medical personnel may use it to gradually promote the standardization of pulse diagnosis....

RECENT INVESTIGATIONS OF PULSE

Chinese researchers have pursued the question of how often certain pulse types are found, particularly with frequently occurring serious diseases, such as cancer and hepatitis. For example, it was reported by researchers working at several institutions in mainland China that (21):

Studies indicate that wiry, slippery, and rapid pulse, or simply wiry and rapid pulse, often denotes exacerbation of the illness [cancer]. When slippery and rapid pulse, wiry and rapid pulse, or weak and rapid pulse appears post-operatively in patients with carcinoma, one should seriously consider the possibility of an incomplete operation. Owing to difficulty in inspection of tongue features of patients with oral or facial neoplasms, physicians often resort to pulse-taking to follow-up the patient, and it is found that the chi pulse is weakened in 50%, and absent in 25% of the patients, which is statistically significant in comparison with the pulse of normal subjects.

In a study of advanced hepatitis patients with cirrhosis or liver cancer carried out in Taiwan, it was reported that most of the patients had a weak pulse on the left wrist at the cun and chi positions, compared to normal subjects (22).

In a broad evaluation conducted in Hong Kong, it was reported that specific pulse categories are more commonly found with the initial stage of illness, versus more developed and advanced stages of an illness (23). The common pulses were:

- Original pulses (initial stage of illness): floating, deep, slippery, uneven, long, short, taut, soft, large, small;

- Changing pulses (serious disease develops): rapid, tense, slow, moderate, full, hollow, indistinct, thready, firm, weak; and

- Very abnormal pulses (critical illness): tremulous, running, knotted, intermittent, tympanic, scattered, deep-sited, replete, feeble, no pulse.

CONCLUSION

Pulse diagnosis is one method of determining the internal conditions of patients with the aim of deciding upon a therapeutic regimen. In order to make use of this diagnostic, the practitioner must learn the proper method of taking the pulse, the factors that influence the pulse, and the categories into which each patient's unique pulse form can be fit. Practitioners must remain especially alert to new factors that influence the pulse readings so as to assure that the results of pulse taking are meaningful. Most authorities agree that in the modern era one must be able to detect a relatively limited basic group of pulse forms in order to utilize the information for devising a therapy (i.e., acupuncture, herbs). These requisite forms determine whether the focus of the pathological process is at the body's surface or interior, is of a hot or cold nature, or is of an excess or deficiency type. The fundamental pulse categories that practitioners are to learn correlate directly with the well-known "eight methods of therapy" (see: Enumerating the methods of therapy). There have been recent attempts to broaden the scope of pulse diagnosis; for example, feeling the pulses immediately after insertion of acupuncture needles has been suggested recently as a means of determining whether the "qi has arrived" as a result of correct point selection and needle manipulation. There have also been attempts to more clearly define the pulse forms; for example, by developing medical equipment that can detect and record the pulse forms, and to develop statistical analysis of pulse types by disease. Pulse diagnosis remains an important part of the practice of traditional Chinese medicine that is still being explored and developed.

REFERENCES

- Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Lectures on essentials of traditional Chinese medicine VI: Methods of diagnosis, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1982; 2(4) 321-328.

- Maoshing Ni, The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine: A New Translation of the Neijing Suwen with Commentary, 1995 Shambhala, Boston, MA.

- Hong-Yen Hsu and Peacher WG (eds.), Shang Han Lun: The Great Classic of Chinese Medicine, 1981 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Yang Shou-zhong, The Pulse Classic, 1997 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO.

- Flaws B, The Secret of Chinese Pulse Diagnosis, 1995 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO.

- Porkert, M, The Essentials of Chinese Diagnostics, 1983 Chinese Medicine Publications, Zurich.

- Xie Zhufan, Selected terms in traditional Chinese medicine and their interpretations (VIII), Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine, 1999; 5(3): 227-229.

- Xie Zhufan and Huang Xiaokai (editors), Dictionary of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1984 Commercial Press, Hong Kong.

- Yang Shouzhong, The Heart Transmission of Medicine, 1997 Blue Poppy Press, Boulder, CO.

- He Honlao, Exploration of the effect of acupuncture on string-like pulse, Journal of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1987; (1): 51-55.

- Hsu HY and Wang SY (translators), Chin Kuei Yao Lueh, 1983 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Unschuld PU, Forgotten Traditions of Ancient Chinese Medicine, 1990 Paradigm Publications, Brookline, MA.

- Gao De, A discussion on selected topics relating to pulse-taking diagnostics, Journal of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1987; (1); 57-61.

- Kaptchuk T, The Web that Has No Weaver, 1983 Congdon and Weed, New York.

- O'Connor J and Bensky D (translators and editors), Acupuncture: A Comprehensive Text, 1981 Eastland Press, Seattle, WA.

- Cheng Xinnong, Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion, 1993 Foreign Languages Press, Beijing.

- Hsu HY, Chinese Herbal Science, 1982 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Hsu HY, A description of the four diagnoses and the eight principles, Bulletin of the Oriental Healing Arts Institute of U.S.A., 1978;3 (2): 17-22.

- Editorial Committee, International Conference on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology Proceedings, 1987 China Academic Publishers, Beijing; 1087-1099.

- Anonymous, Essentials of Chinese Acupuncture, 1980 Beijing Foreign Languages Press, Beijing.

- Yu Guiqing, et al., New progress in the four diagnostic methods of cancer, Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 1990; 10(2): 152-155.

- Chan Yensong, et al., The pulse phenomenon of liver cirrhosis and hepatoma, Journal of Chinese Medicine 1992; 3(2): 13-21.

- Huang Huibo, New theory on pulse study, in International Congress on Traditional Medicine Abstracts, 2000 Academic Bureau of the Congress, Beijing.

0 komentar:

Posting Komentar